Artist Bio

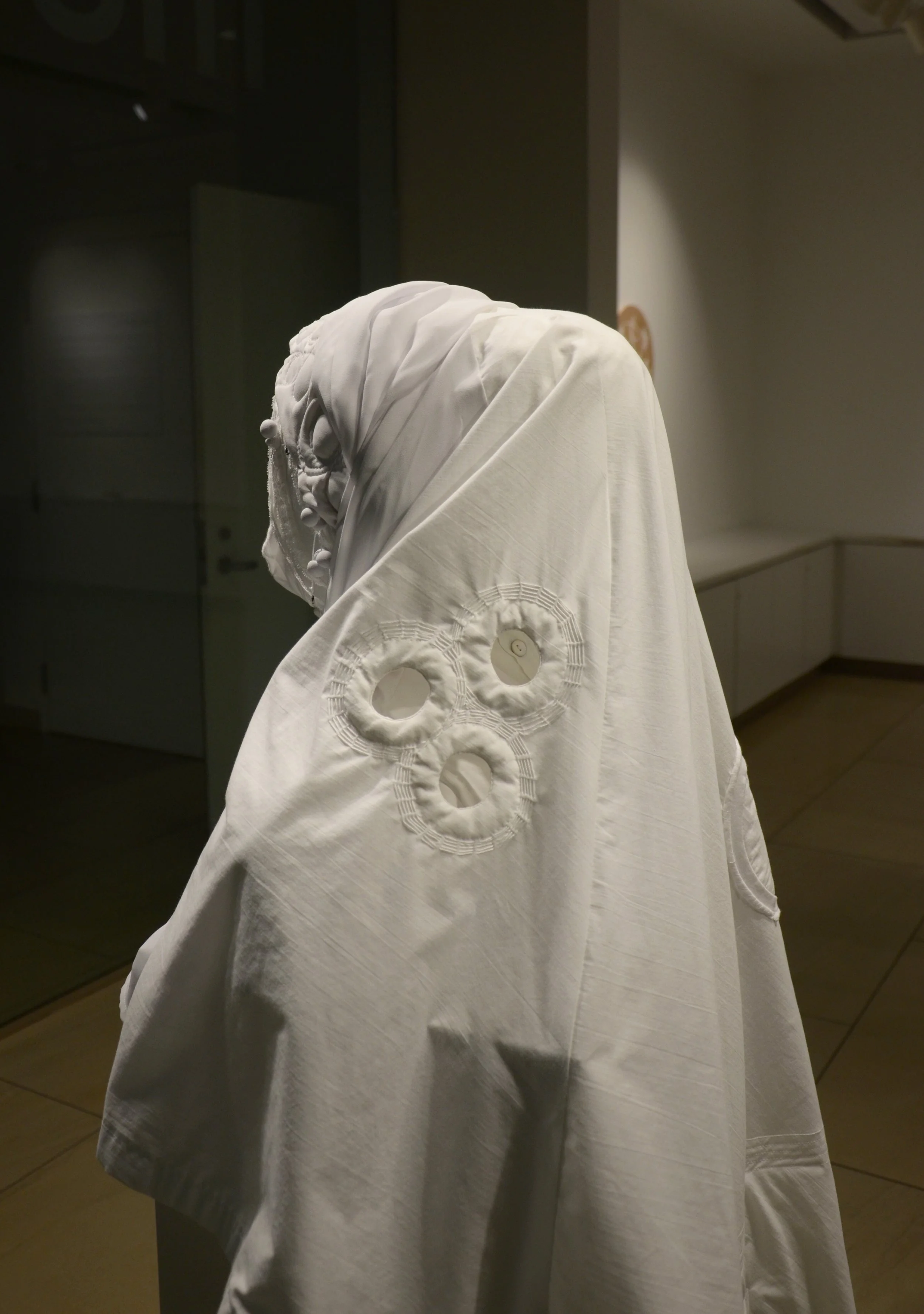

Muhajir رِجاَهُم Émigré

by Hawa Stwodah

14” x 18” x 36”

Assortment of discarded textiles (natural and synthetic blends of cotton, ramie, polyester, nylon)

This work is a part of an ongoing series exploring identity, perception, surface design, and materiality.

For this piece, named Muhajir or Émigré, I established specific parameters: to create solely with white and off-white textiles sourced from the community donation boxes (part of the project), and to employ hand-sewing techniques rooted in traditions spanning Western and Central Asia to South Asia. These constraints emphasized the reuse of materials and the endurance of traditional craftsmanship across time and geography.

The understructure of the piece began with a head-and-shoulders form I’ve used in recent work. I molded plaster of Paris–soaked cotton strips over the form to create a skeletal frame, later cutting and refitting it to evoke a bowed posture. On this base, I composed a textile layer, referencing the musculature of the head and shoulders through pieced and quilted fabric. Buttons, cording, and batting—salvaged from the discarded garments—were repurposed as integral components. A draped veil envelops the head and shoulders, binding the form within its own quiet enclosure.

Across the surface, I worked with motifs long associated with protection, continuity, and renewal: whorls, spirals, Chintamani, circles, ram’s horns, pomegranates, and the tree of life. These symbols, executed through appliqué, drawn thread, topstitching, trapunto, couching, and satin embroidery, echo the shared aesthetic vocabularies of multiple regions. The veil features an exaggerated abstract interpretation of the quarter-square triangle quilt pattern. Around the face, I added lace appliqué, ribbons, and ornamental buttons, gestures of adornment and reverence.

The facial area is overlaid with a textile panel produced through drawn-thread techniques, with a circular pattern referencing the mesh-like eye region of the Afghan Chadri. These design choices integrate influences from regional apparel and reinterpret the notions of concealment and exposure.

The inspiration for this piece came from three sources. The first was historical research on sacred garments housed in Istanbul’s Topkapi Palace and the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts, specifically the textiles attributed to Sayyidah Fatima Zahra (RA). A 2015 visit to view her blessed robe left a profound impression. Years later, her bridal veil was displayed in an exhibit, and although I couldn’t see it in person, the images available online further shaped the project’s direction.

The second influence came from traditional surface design practices, many of which were drawn from my own archive of quilts and embroidered household textiles. These include early-1900s family quilts from the American Pacific Northwest, Central Asian wall-hangings, pillows and carpets collected in the 1960s and ’70s, and handmade patchwork quilts produced in Virginia in the mid-1990s.

The final is my ongoing inquiry into displaced people, resilience, and adaptive reuse in material culture. I am drawn to how displaced peoples—across place and space—carry fragments of home with them. The Arabic term Muhajir means “migrant,” initially referring to the early Muslims who left Mecca for Medina with the Prophet Muhammad (Peace and Blessings be upon Him), His Family, and Companions. Reflecting on Their journey, I wondered what garments and possessions they took, how these items transformed in a new city, and how care and maintenance became acts of survival and faith.

These questions extended into a broader investigation of displacement and diaspora. While visiting relatives in Ireland, I encountered local histories of migration during the Great Famine and viewed Rowan Gillespie’s sculptural figures at Dublin’s Custom House Quay. Their depiction of individuals carrying cloth bundles recalled the universality of migration narratives. My relatives came from Ireland to the United States during that period, and later generations migrated westward across the country. Quilts and household textiles from those journeys—documented through journals and photographs—are still treasured by my family. Later in the 1980s, my family and I came to America under duress and encountered experiences like those before me.

Muhajir integrates these historical and personal references into a single constructed form. The materials, all repurposed and hand-stitched, reflect traditions of conservation and adaptation found among displaced communities. Generations later, quilt patterns and mending practices that emerged during those migrations remain in my family’s care. These material traditions, rooted in necessity, evolved into a language of resilience.

Muhajir, then, is both homage and inquiry. It reflects my fascination with how textiles carry faith, memory, and identity across distances—how the act of stitching can bridge the sacred and the everyday, the historical and the personal. Each seam becomes a line of connection, binding fragmented histories into a single, embodied form.